“Reparation is a construction project…. It was never entirely, or even primarily, about money. The demand for reparations was about social justice, reconciliation, reconstructing the internal life of black America, and eliminating institutional racism.”

— Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò, Reconsidering Reparations

CONSTRUCTIVE REPARATIONS

Curriculum: Advanced Architecture Studio, Fall 2025

Professor: Janette Kim

Studio Partner: EVOAK! (Randolph Belle and Jeremy Liu)

Related Programming and Curriculum: 980 Block Party

Students: Students: Salim Ahmed, Noor Alhashimi, Vicky Cheung, Yicheng Eason Jiang, Finn Ghinn, Amanda Gomez, Lesly Karina Gonzalez-Benitez, Amira Seale, Curran Thompson, and Samuel Avila Vallejo.

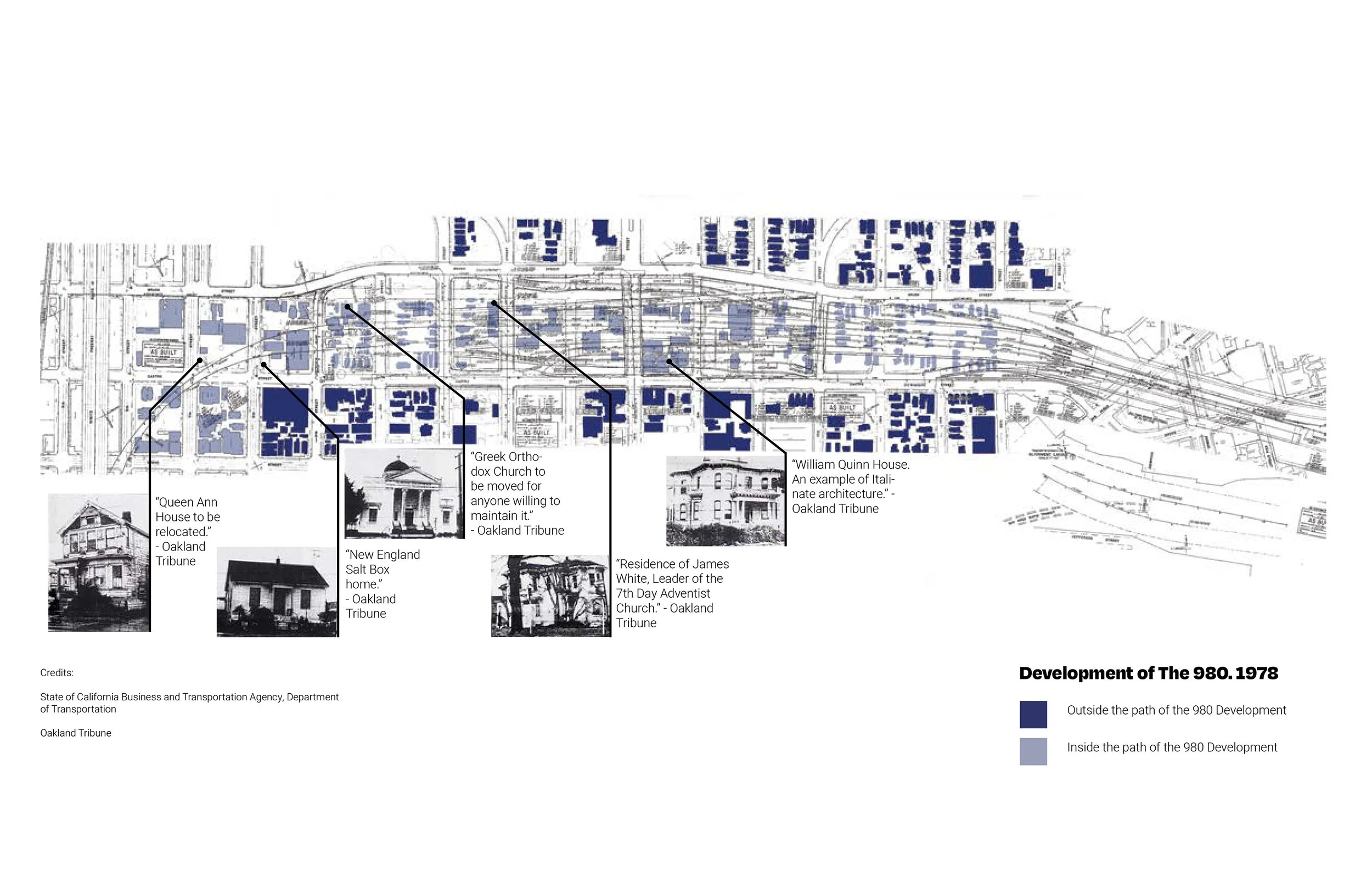

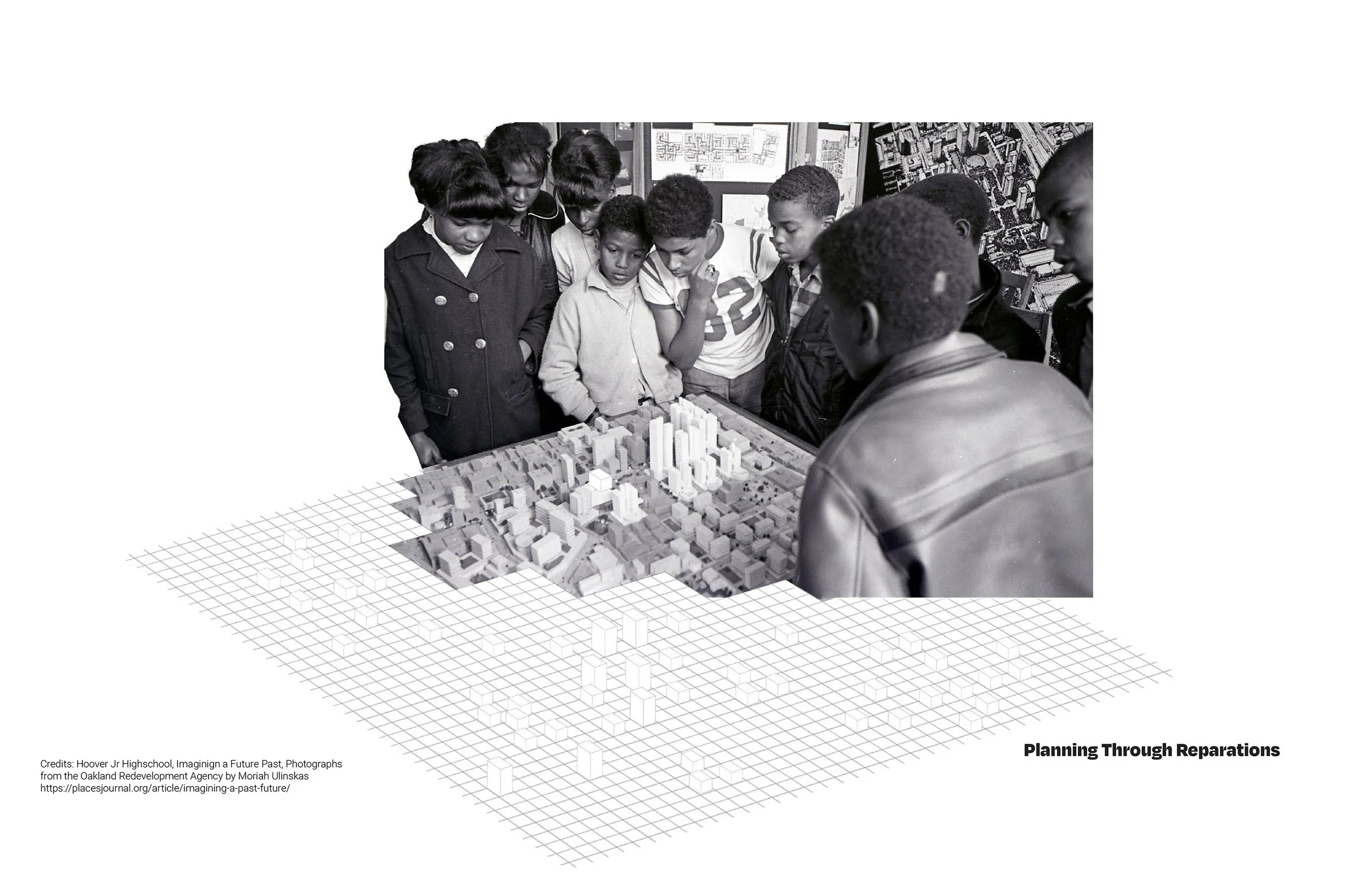

This studio worked with Oakland community members to imagine how the I-980 freeway can be reclaimed a form of reparations. We were inspired by philosopher Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò’s vision of constructive reparations, which imagines repair as a blend of direct compensation at an individual scale and systemic change at a collective scale. We studied interviews with legacy residents and archival material of the lives and livelihoods disrupted by freeway construction from the 1960s to 80s. We then designed ownership and investment strategies that could return power, land, and resources to West Oaklanders. Students designed a 2-block stretch along the freeway, between 12th and 14th streets. Projects return land to Afro-Indigenous communities, incubate wealth creation through youth-led initiatives, and still inventive models of housing ownership driven by community governance. We hope community members will see this work as a conversation starter to support and inspire future action led by grassroots action.

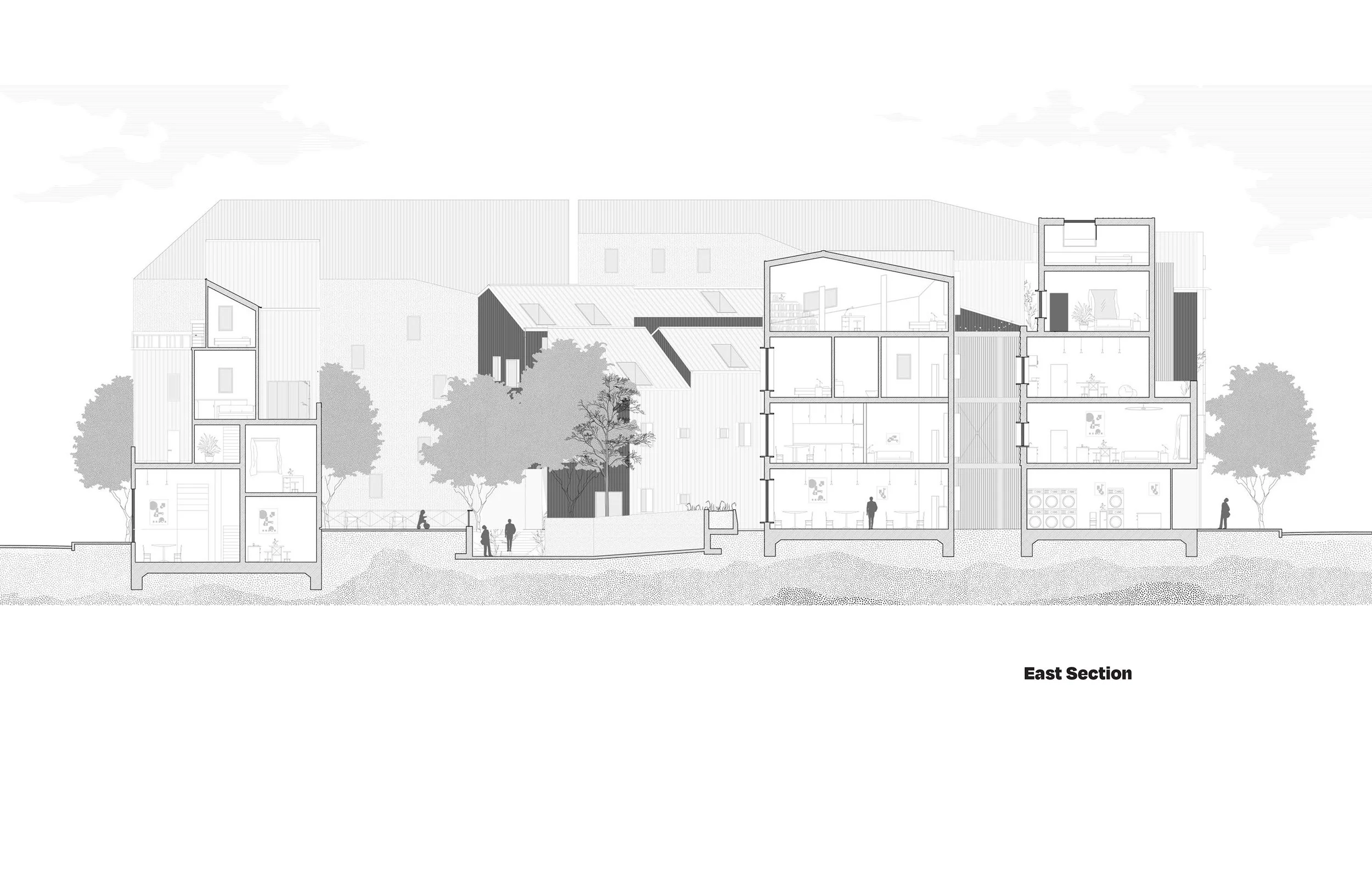

Feeling Like Home

Finn Ghinn and Noor Alhashimi

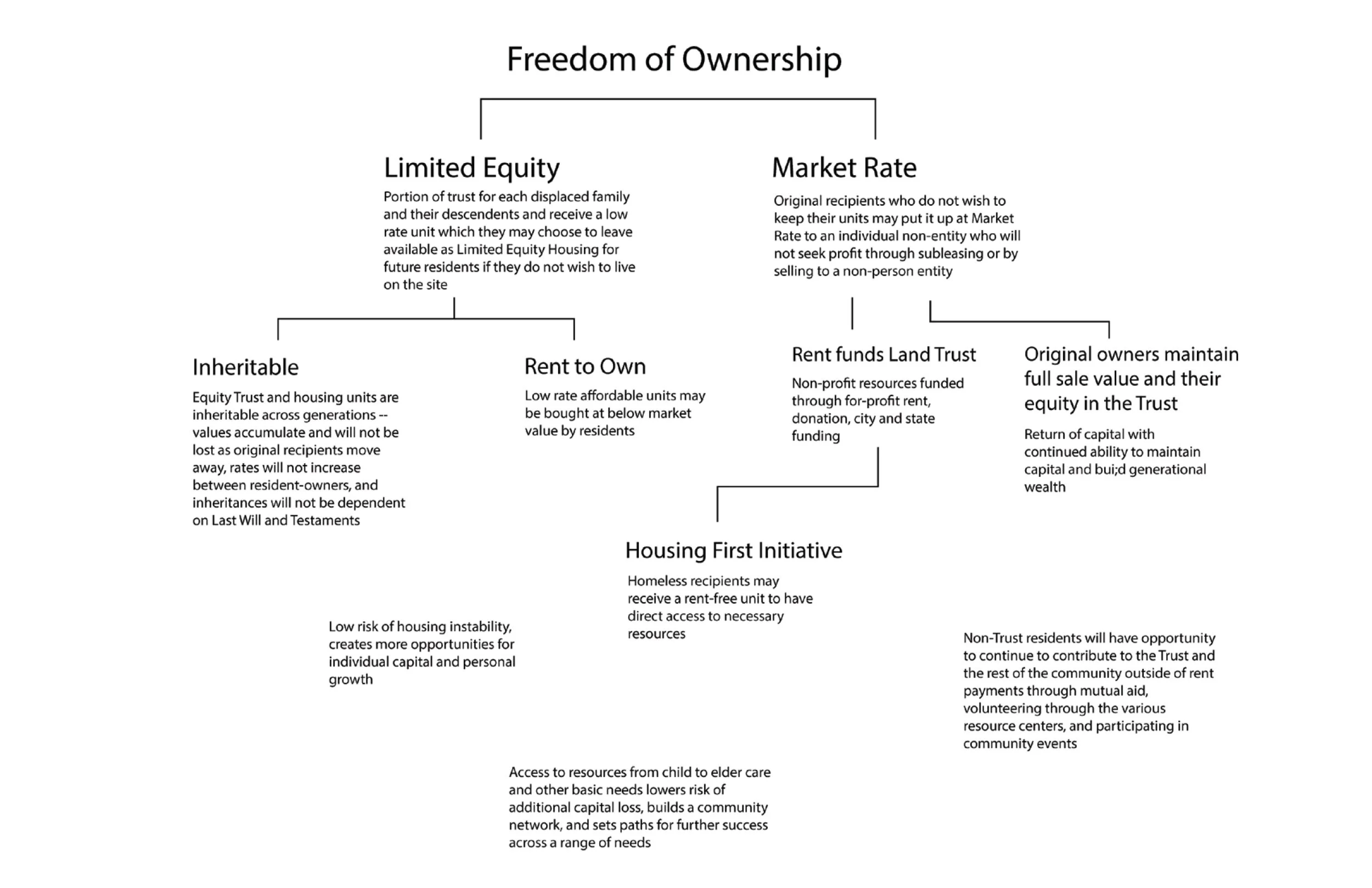

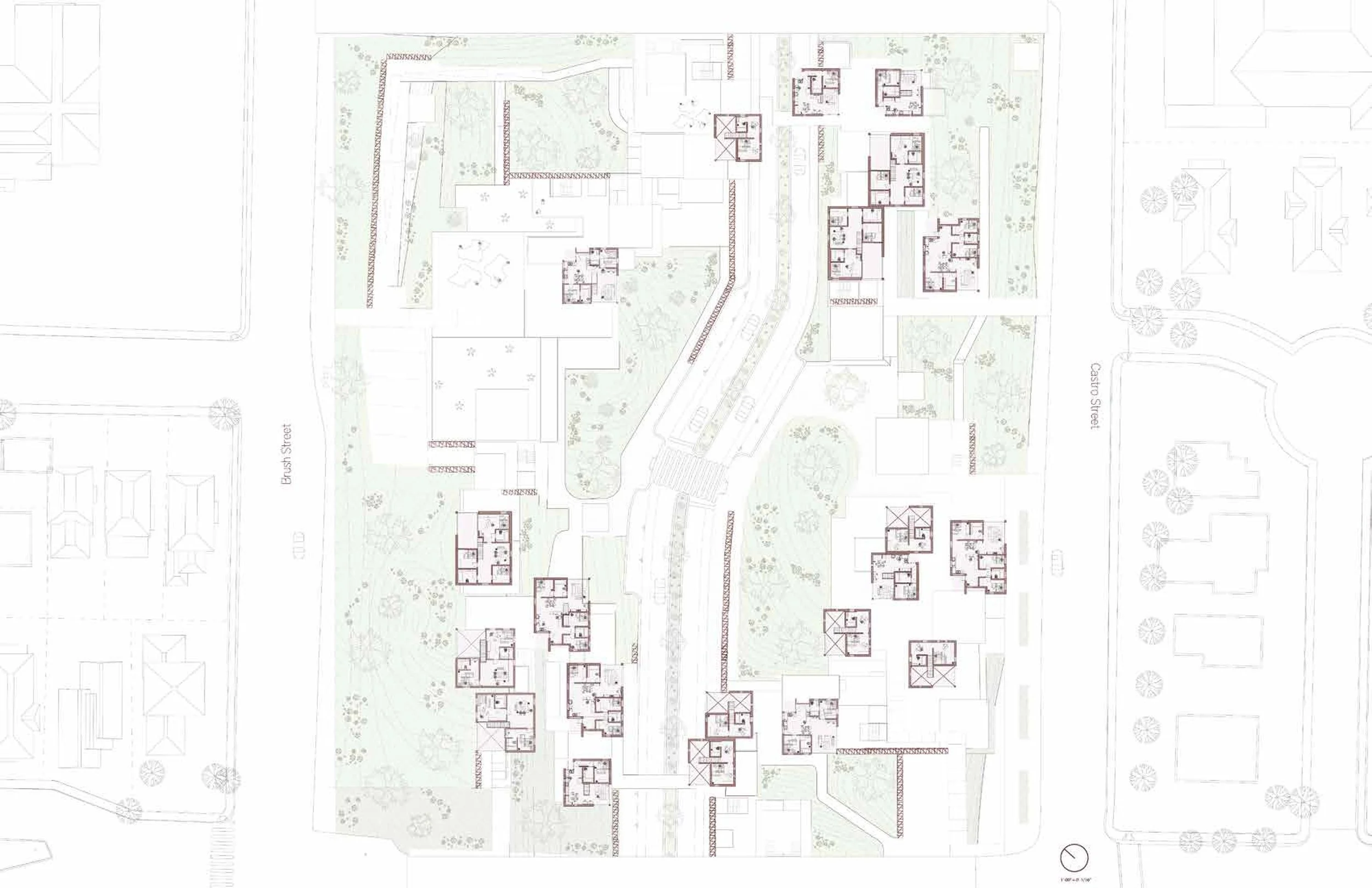

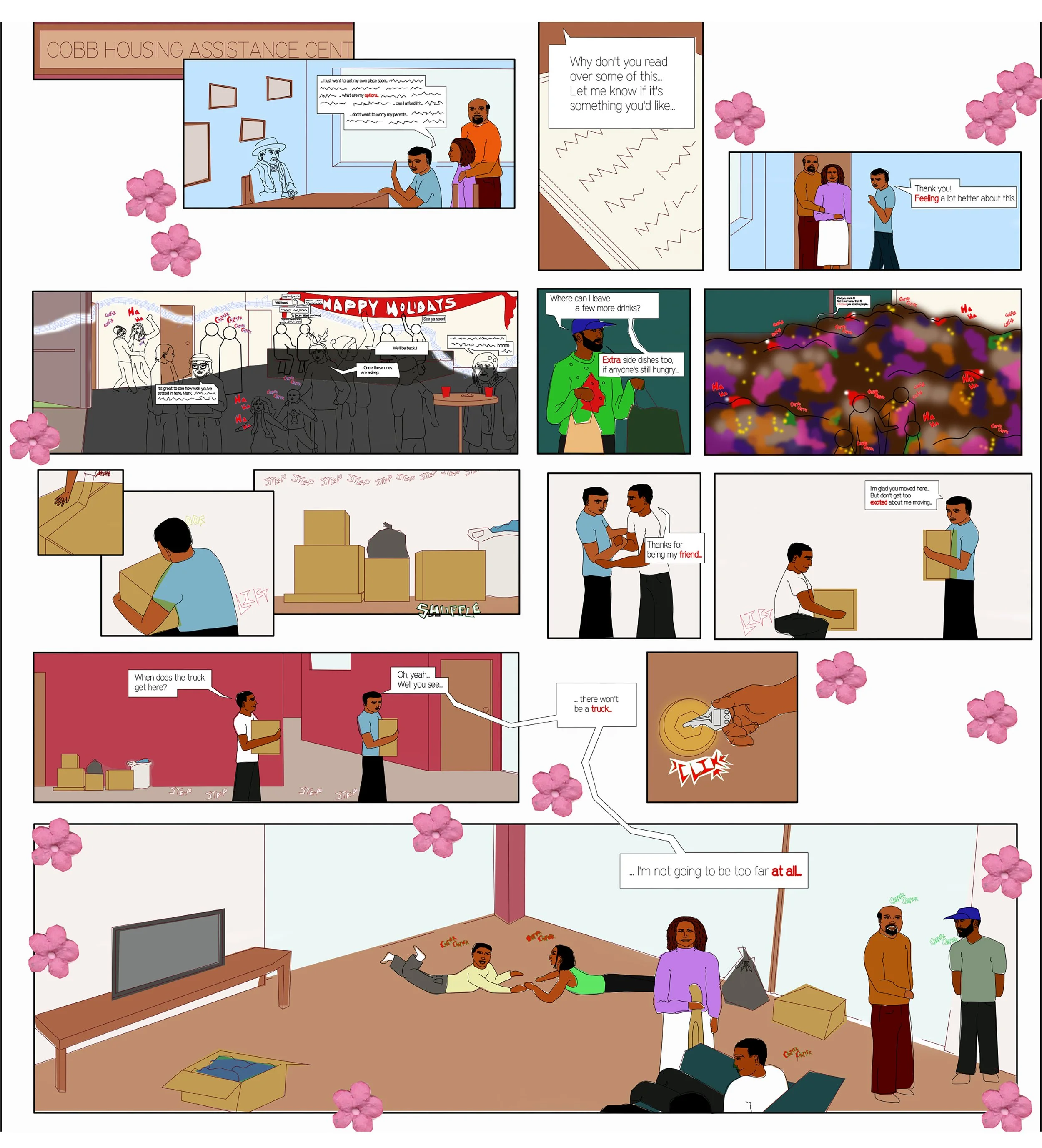

What kind of wealth can reparations build? Feeling Like Home explores how reparations can build wealth while giving legacy residents the freedom to determine what wealth means to them. This project proposes a new kind of ownership model, called a Mixed Equity Trust, in which residents can choose whether to shelter their homes from speculation (by agreeing to limited equity, or restricted profits on their units, in exchange for long-term affordability) or build monetary wealth (with an option to sell their property on the free market). All living units–both for-profit and not-for-profit–are mixed together in clusters and shifted spatially to create communal spaces between neighbors. Units range from single to six bedrooms to accommodate a broader range of family types and needs. Below, the land beneath these units would be owned by the community as a whole. This project downsizes the highway into a boulevard and sculpts the current grade of the 980 freeway into a landscape with gardens and gathering spaces. Retail, social services, amenities, and community spaces open onto multiple courtyards to repair social bonds disrupted by the freeway.

Land Back.

Amira Seale, Amanda Gomez, and Karina Gonzalez-Benitez

Who is reparations for? The Land Back project acknowledges land as a form of reparative currency that returns ownership to Ohlone and Black West Oaklanders who have both endured the hardships of displacement, erasure, and disconnection from their communities. Sited on the I-980 freeway in West Oakland between 12th and 14th street, it reclaims ground where the community once flourished in safe public spaces. The project references the blurred territories that the Ohlone used as a basis for softening a city grid of harsh boundaries, while simultaneously centering spaces that nurture connection, such as grocery stores, housing, small businesses, and community centers. Land Back reimagines ownership as a shared, intentional practice, with new types of strategies including models that represent what is “yours”, “mine”, and “mine-ish”; building a foundation for longevity, local value, and a community-driven economy that West Oaklanders deserve.

Reparative Voids

Curran Thompson and Sam Avila Vallejo

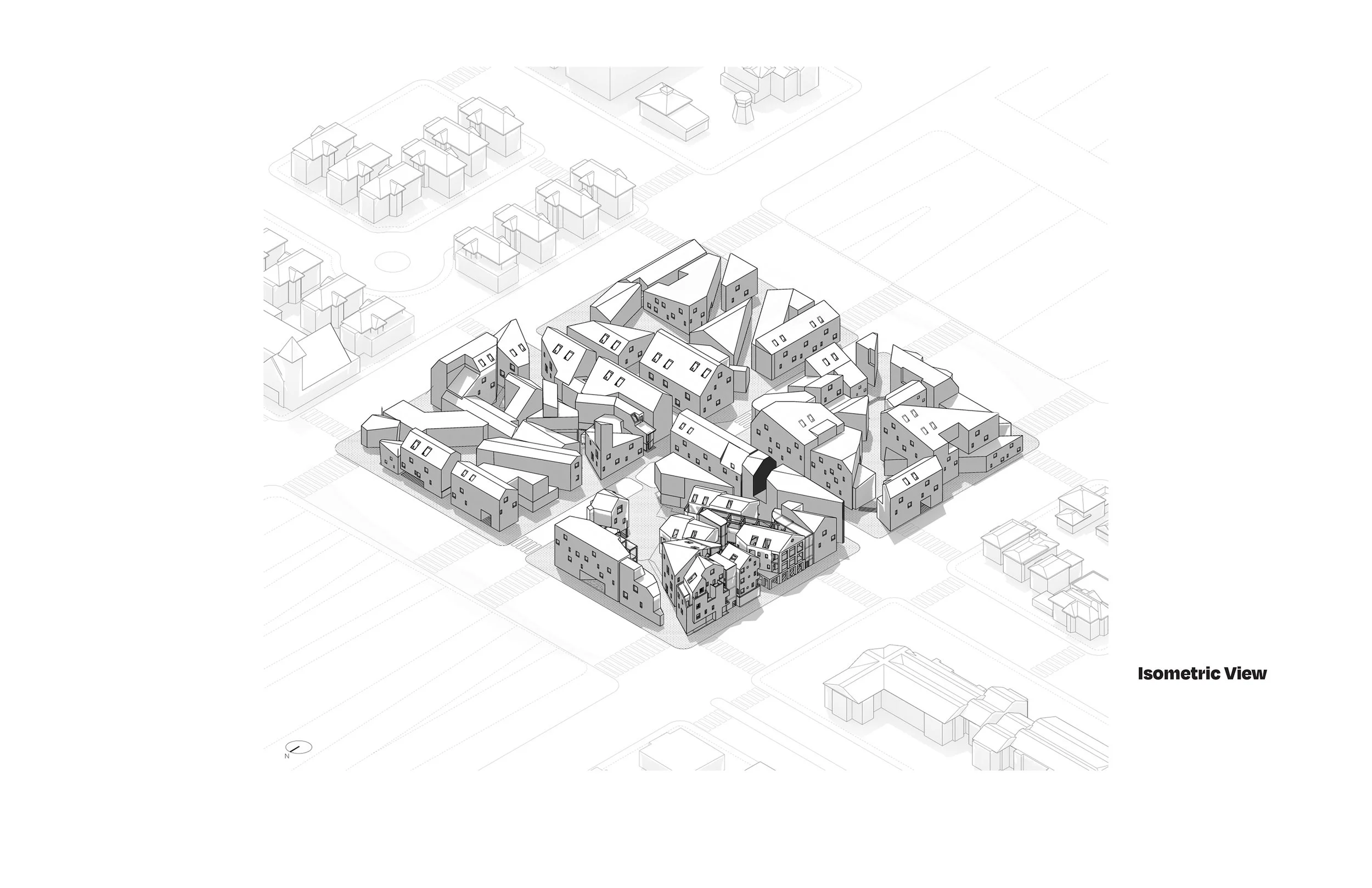

How can reparations prompt grassroots change? Reparative Voids studied the diverse building typologies erased by the freeway. Sam and Curran echo the voids left by urban renewal by carving up their new city block, but repair this loss by restoring a vibrant mix of uses, scales, and household structures. Here, in these new voids, residents can interact and support each other.

Worker Cooperative for the Future

Vicky Cheung and Yicheng (Eason) Jiang)

How can reparations build a sustainable local economy? This project reimagines the I-980 corridor in West Oakland as a site of reparative urbanism rooted in youth empowerment and cooperative ownership. Rather than treating the freeway scar as neutral infrastructure, the design acknowledges its history of racialized dispossession and proposes a phased strategy that rebuilds community power through education, production, and collective decision-making. A porous public surface spans the downsized freeway, creating new civic space while supporting a modular system below and above. Across three phases, workers cooperatives grow from educational programs to small-scale manufacturing and finally to a self-sustaining retail economy shaped by local youth. The architectural system adapts over time, allowing community needs and cooperative enterprises to evolve. Ultimately, the project transforms a space of harm into an integrated social, economic, and physical framework that reconnects West Oakland to downtown and supports a future led by the next generation

Boulevard Rising

Salim Ahmed

Boulevard Rising emerges from direct engagement with community histories and everyday practices, not abstract master planning. In listening to legacy residents, the project reframes a long-standing infrastructural barrier into an urban condition that supports daily life, economic activity. It embeds incremental, accessible programs along a new public spine that serve local routines, commerce, and rest. It does not rely on speculative redevelopment but on spatial strategies that enhance continuity, visibility, and civic exchange, giving long-term residents tangible improvements to mobility, access, and public life. By prioritizing human-scaled places for gathering, informal trade, and movement, Boulevard Rising supports equity, local stewardship, and collective creation, while acknowledging the histories and rhythms of those who have long shaped the city’s social fabric.